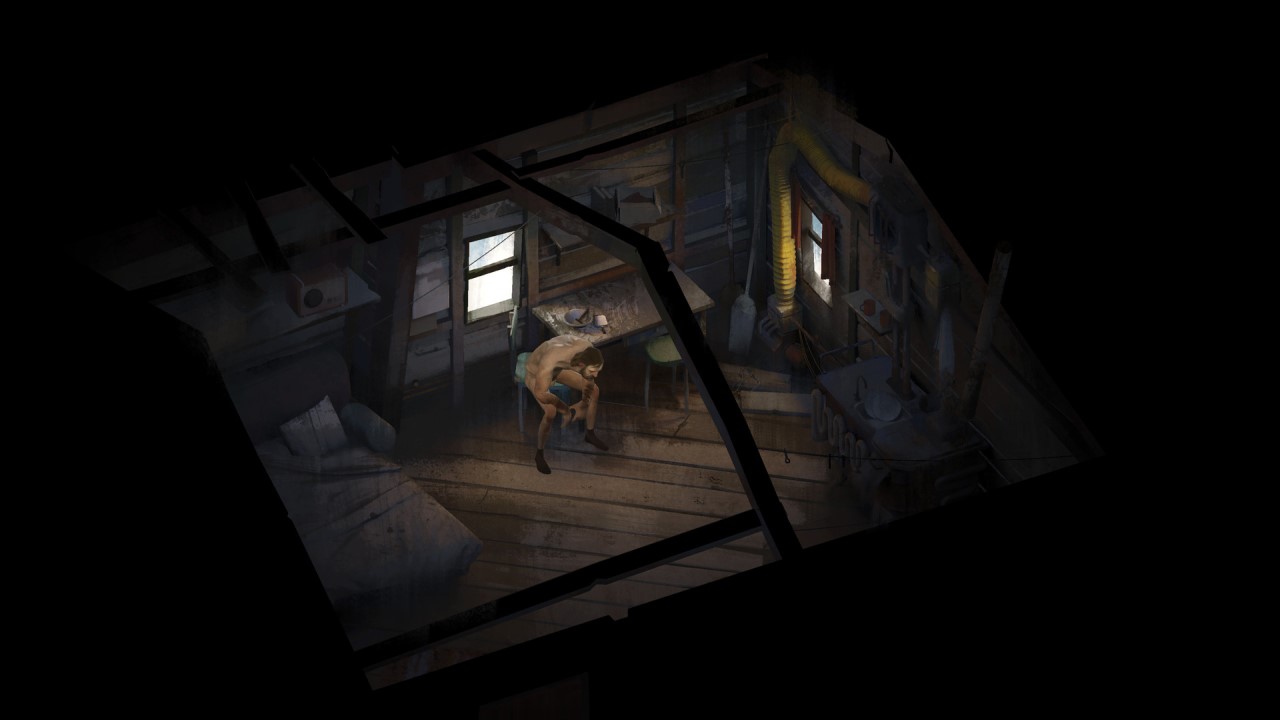

I wake up with a hangover so intense I wish I was dead. My Ancient Reptilian Brain even suggested as much as it tempted me to remain in the inky blankness of oblivion before I opened my eyes, and my Limbic System didn’t protest the suggestion. Despite this, I rise from the dirty floor of my hotel room feeling like the apocalypse. As my vision comes to I notice the dingy abode I woke up in is in a state of absolute chaos, with bottles strewn about like cockroaches in a greasy diner.

Holding my head in my hand, I stumble about and grab the various bits of clothing dashed about, trying in vain to remember how I got here; I drank myself into such a stupor that I’ve lost my memory. I slowly find my brown party pants, my stained shirt, and a single crocodile leather shoe; it’s partner went missing in the night. Looking up I see an insidious necktie hanging from the fan, swirling about in solitude.

I reach up to pluck it from it’s perch, only to find myself confronted with the first of many, many skill checks in Disco Elysium. I attempt to grab the tie without first turning off the fan – I feel confident with my fifty-eight percent odds of success – and I fail, losing my sole pip of health. I’m rewarded with a heart attack for my efforts, and I die. Fade to black, baby: no more pain.

Any other RPG would have simply given me some flavor text, patted me on the ass, and hurried me on my way towards my ultimate destination: completing the game. But developer ZA/UM isn’t concerned with adhering to decades of video logic, of providing a story with a variety of largely inconsequential choices. Instead, they let me kill myself in the first five minutes, because I decided at the outset to not focus on my physical traits. I reached for a tie, failed, and died. Cut to credits; thanks for playing.

It’s all disco, baby.

For the uninitiated, Disco Elysium is a CRPG detective story, in which you inhabit the battered flesh of a man with no memory, all because he went on the world’s (arguably) greatest three day bender. It’s on you to solve the crime he has been tasked with investigating, all while piecing together the shattered remnants of his psyche. The amnesiac trope may be tired, but the approach ZA/UM uses is not only novel, but important: it’s clear this character has an established past, has endured terrible things, and tried to drown them all at the bottom of any bottle of booze he could grab. It’s now on you to determine who he will become in the wake of this mind-shattering hangover, and unlike similar games, Disco Elysium allows you to truly shape him as you see fit.

Choices matter in Disco Elysium, even the mundane. There is no “Character A will remember that,” here. This is a game that will allow you to fail, and force you to handle the fallout. Sure, there is an ultimate “end” to the game, but how you get there can play out in a myriad of different fashions. Disco Elysium isn’t concerned with providing you safety nets that mask your poor choices; that keep you on the “critical path.” And it all starts from the top.

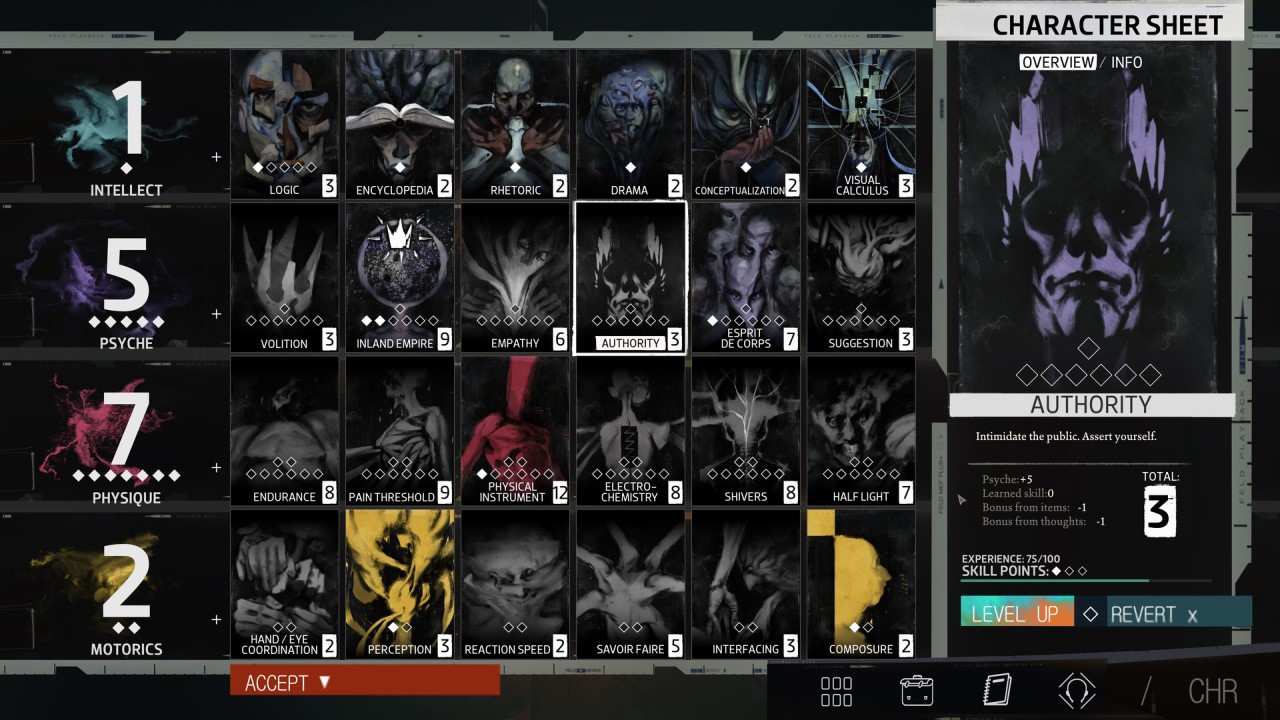

You open the game by selecting either one of three predetermined builds, or by crafting a custom one. There are four attributes in the game (Intellect, Psyche, Physique, and Motorics), and you can opt into a Sherlock Holmes-esque Thinker with a full encyclopedia in your head, a Sensitive detective akin to Twin Peaks Dale Cooper (with your own Inland Empire), or a Physical brute who uses their fists and laser-point aim to settle disputes. If none of those tickle your fancy you can craft your own amnesiac detective by choosing which of those four trees you want to focus on, and then cap it off by choosing a key skill, one that will guide and support your throughout the game.

I mean that quite literally, by the way. Your “skills” in Disco Elysium are not simply numbers you raise to overcome the various skill checks, though that does factor in. Rather, Skills double as your companions in Disco Elysium. The erstwhile Detective Kim Kitsuragi will often be at your side, but your skills – the voices in your head – never leave you alone.

I went with the sensitive build, and both my Volition and Inner Empire would chime in during conversations, or pull me aside with an epiphany. Your skills are the various aspects and modes of your mind, and they are a chatty bunch. The skills you focus on are the chattiest, and they will constantly chirp in your ear, giving your build choices more weight than a simple statistical boost ever could. I dumped points into my physique skill Shivers, the trait that allowed me to be attuned to the world at large, where even a rustle in the wind could lead to revelation. Shivers would pull me aside on a cold night, and ask me to feel the city of Revachol, to take in and absorb the very soul of it. This wasn’t just fanciful world-building; it often led to clues or insights concerning my investigation.

Your skills are your allies, and like any set of allies they can both assist and mislead you. Skills have their own checks within conversations, and the more points you place in a skill the more likely its negative quirks will show. High Logic made me whip-crack intelligent at deducing falsities, but it was a cold and unfeeling bastard by the end of the game, always in conflict with Empathy. Drama developed a penchant for lying, and Half-Light (my flight-or-flight response) was constantly on edge. My Electro-Chemistry craved drugs, booze, and nicotine, often chastising me whenever I turn away from the bottle.

Because, damn it all, I was gonna reform myself. No more drinking; we’re cleaning up! These skills don’t just monologue or spout canned responses at you, they grow with you and adapt to the path you take your detective down. Do you play an Apocalyptic Cop, preaching the world is about to end? Are you a reformed Boring Cop, who is trying to sober up and crack the case? Disco Elysium is all about dialogue – both internal and external – and you’ll often prove who you are with what you say. Nothing is overtly colored with a “this is the good cop choice,” or anything like it. Sometimes asking a person all the questions on offer will push them away, as they begin to see you as an unstable, contradictory mess of a man.

Your skills reflect and internalize your choices in dialogue, often asking you who you are, and who you are trying to be. Are you espousing fascism? Are you are too comfortable sitting on that Centralist fence? Expect a skill to call you out on it, or maybe even try to tempt you into those philosophies further. The skills in Disco Elysium perfectly capture the concept of a mind that never, ever shuts up. The system not only works to further build your character, shaping his inner monologues and how he processes the world around him, but to further apply weight and meaning behind the various choices and skill-checks made in Disco Elysium.

Dance to your own tempo.

And there are thousands of choices to be made, both large and small. Who you talk to and when you talk to them matters; what you say, what questions you ask. All of these basic dialogue options posses genuine heft within Disco Elysium, well before you undertake a skill-check. I was often reminded of traditional tabletop while playing the game (which ZA/UM openly admits influenced the game), and how much more flexible it is over video games.

To break away from Disco Elysium for a split-second, I say this because video games are notoriously binary. They like to signpost their options, and their possible repercussions. They ultimately pull the wool over our eyes, leading us to believe our choices will have consequences, when in reality our choices have little effect on the final outcome – whether that outcome is at the major or minor scales. The goat will still be found, the maiden may or may not live, but we move on to the next scripted story-beat.

Traditional tabletop, like Dungeons and Dragons, relies on the whims of the Game Master and the creativity of the players. A good GM is flexible, but strict. They know their setting, they understand the logic within it, but they allow their players to make impossible or stupid skill-checks to better push against the walls; to see what will and won’t break. And if those players somehow succeed where they should have failed? The GM adapts, and plays along with the improvisation, all while maintaining a steady, guiding hand over the whole ordeal. Rarely do games offer this level of boundary-breaking, while exceptions like Divinity: Original Sin 2 find praise because they offer up the closest representation of this ideal.

Disco Elysium doesn’t just overcome this hurdle, it catapults over and beyond it.

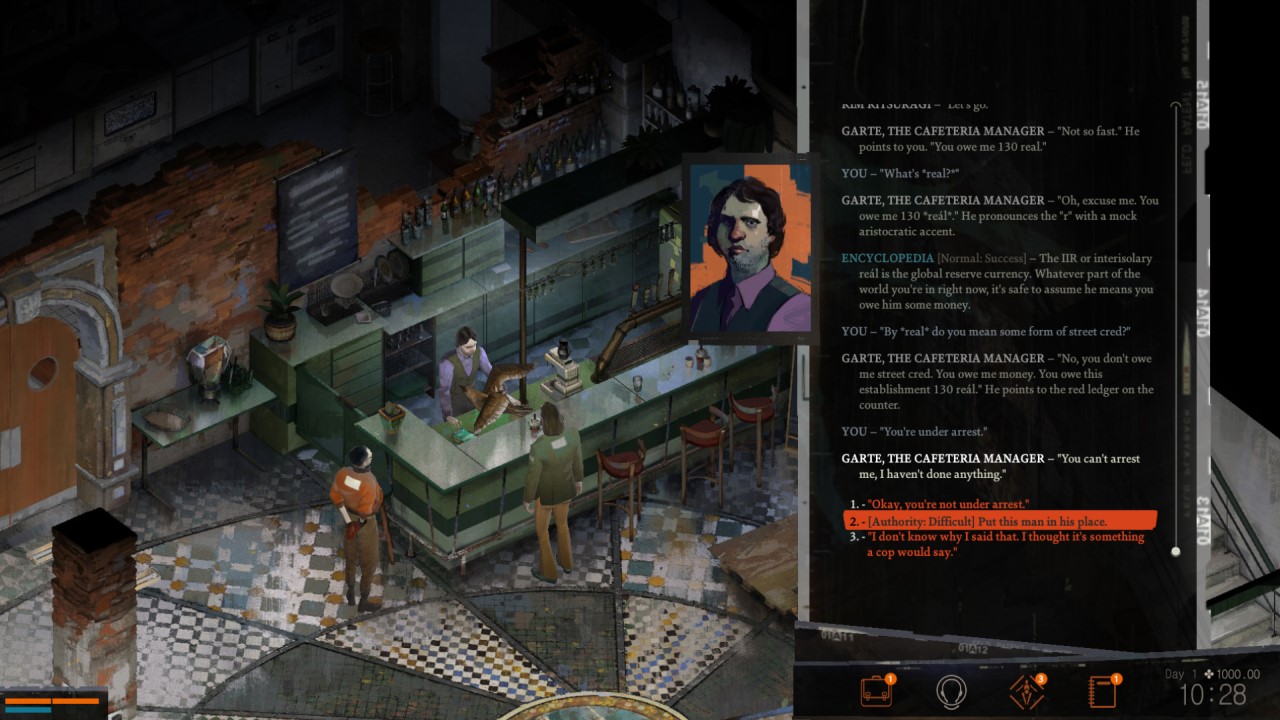

If skills supply the chorus with their chatter, then the diverse array of options and skill-checks in the game provide the rhythm. As I’ve already noted, dialogue isn’t the usual “choose all the options” affair, in that you can get away just fine contradicting yourself. Disco Elysium holds you accountable, and often not asking the question in your head is the way to go. You skills will often chime in to tell you what to say, and what to avoid, but it’s on you to choose whether to trust them or not. They can be wrong as likely as they can be right, but whatever you choose you need to live with it, even if Logic apologizes for the poor suggestion.

Furthermore, every action in game is determined by the roll of the dice, much like a traditional tabletop game. It’s simple in execution: exceed or match the roll to succeed. Where Disco Elysium breaks with video game tradition is that failure is intentional. Some skill checks are set against impossible odds, and while you can equip different clothing to boost stats, or use drugs for temporary boosts, you can’t alter those mid-conversation. The majority of skill-checks can be repeated, but only after leveling that skill. Some – the red checks – stay failed forever.

ZA/UM wants you to fail skill-checks and to specialize your stat sheet, because they are smart GMs. They know how to pivot around your mistakes, and they understand that not every choice should lead to the same outcome. If you can’t get a body out of a tree on your own, the game will provide you an alternative, but you may not like it. Press further down this line, and you may even find yourself doing things you didn’t want to do with the local union boss, but a successful check can cut those events out altogether. Or, leave the body in the tree. Fuck it, your call, but you may not be able to find your missing gun.

Or, maybe you will, because you’ll find yourself at the right place at the right time. That’s the most nebulous of scenarios I want to provide, because Disco Elysium is best left unspoiled. The point being: your choices are not a binary “I passed this check; body comes down – I failed this check; body comes down, but gruesomely.” While those diametric choices exist, they exist as logical routes against a variety of additional routes. Maybe you want to get the body down in a gruesome manner, and you can do that. But it’ll likely bite you in the ass later, and block off other routes for other choices.

Disco Elysium is a branching web of choice, consequence, and alternatives, and it’s largely because the skill-checks are designed to rewards players who don’t save-scum their way through the game. ZA/UM wants you to roleplay here, actively roleplay. If you don’t want to do something, you don’t have to. Time progresses naturally throughout the game, and there are a set amount of days to finish the investigation, so waste them by reading a book in your hotel room if you so choose; ZA/UM doesn’t care. Don’t expect anything to end well, but by all means, they’ll let you do it.

What you do, how you do it: it all spirals out and away, but ZA/UM manages to keep it under control. Your decisions come around in unexpected ways, sometimes with people you didn’t expect them to affect. Words of condolence can reappear to haunt you with a later character who didn’t quite care for your sympathy. Siding with one person over another may block off entire routes you could have ventured down.

This is all bolstered by some of the best writing I have ever seen in not only a video game, but prose in general. Each one of your skills has a voice unique unto them, and the characters themselves fair just as well. Strong voice-acting brings all of this to life, though you’ll still do plenty of reading in Disco Elysium. It’s absolutely mental how much, in fact. Apparently there are over one-million words in the script, and I believe it. Your inner monologues, the diverse selection of dialogue choices, and all the various ways you can splinter and fracture the game means there is a wealth of fantastic writing to drown yourself in. ZA/UM’s dedication to roleplaying is evident in the script, with much of what is said or seen proving unique to you, and how you are playing your detective.

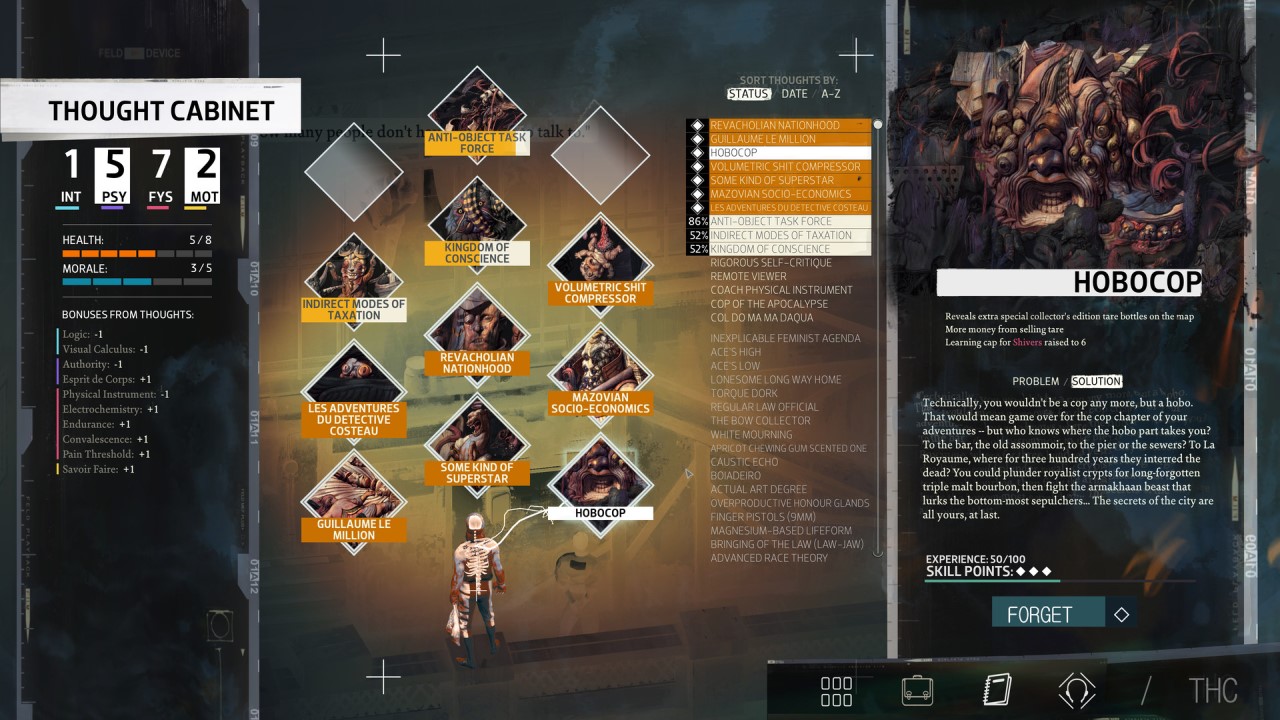

On top of all those options, ZA/UM cements Disco Elysium’s roleplaying fantasy with the ability to internalize and process your thoughts within a Though Cabinet. As you play the game, you’ll come across certain people, dialogue, or passive observations that will trigger an internal thought. If you choose to internalize it, you’ll wait a set amount of time in-game to earn a passive buff or debuff, but it’s the writing and artwork for these thoughts that makes them special. It’s like peering into your own mind as you rationalize your own memories and experiences. Each thought has an intro and a revelation, and the game-y numbers side of them feel connected to the thoughts themselves.

The Thought Cabinet, when placed alongside all these other roleplaying systems, completely sells the illusion of being inside someone else’s head. You’re detective is a real person, who had real dreams, and suffered real personal tragedies. How you play him will determine who he was, and who he will become. No one playthrough of Disco Elysium will be the same thanks to ZA/UM’s dedication to building a role-playing game foremost; not a video game with role-playing features.

Here is the best bit, however: they still managed to make an amazing video game underneath all that roleplaying.

The world may be ending, but who cares.

Disco Elysium takes place in the city of Revachol, fifty years after a failed Communist uprising. More specifically, it takes place in the Martinaise district, an area of town that has become the bastard step-child no one wants. After a recent hanging, your detective has been sent in to investigate, along with a cop from a competing precinct, because neither yours or his has settled on who actually polices Martinaise. The whole area is a run down shit-hole rife with crime, poverty, and post-war agony. The ghosts and regrets of that failed uprising linger in Martinaise. Old men play a game in the old craters left behind from the coastal invasion in the war. Buildings are pocked with bullet holes, and an intentionally distressed statue of the former monarch rests silently in the center of a shipping blockage.

The muted, damp aesthetic will sometimes give way to splashes of color, and in these moments there are signs of life and rebellion. A teenager sits on a balcony with red paint, contemplating what she wants to graffiti. Your partner’s vehicle is a sharp blue against the snow and dirt smeared road. The world of Disco Elysium looks like a post-USSR Soviet Bloc city painted over with deliberate, delicate brushstrokes. The whole game has this painterly look and feel to it, and every square-inch of it appears to have been designed with care and love. It’s clear ZA/UM is deeply affectionate towards their setting, and it shows in every broken window, boarded up building, and dejected tuft of grass.

The world of Disco Elysium feels lived in, even if those living in it wished they didn’t. The handcrafted setting doesn’t repeat itself, and the layout of the map feels logical and cohesive. This was a portion of the city left alone for fifty years, and a sinking sadness blankets the whole area. This mood is further elevated by the excellent soundtrack, one that drives home the depressing decay all around you. Subtle rhythms cry in the background as you explore Martinaise, a melancholy chorus of voices humming under the discordant strings. There are livelier tracks for when you choose to be less somber, and there are tracks that will crush your soul when played in tandem with certain events. The soundtrack is emotionally evocative, and used with expert skill in concert with the story.

And what an amazing story it is. Again, I don’t want to spoil too much here, but how you move about solving the crime, who you interact with: Disco Elysium’s writing isn’t just great, it’s impactful. You’ll be forced to reckon with not only your choices on a personal level, but how they affect the world altogether. ZA/UM has handsomely stuffed Disco Elysium with intelligent world-building, ensuring it works in perfect synchronicity with the narrative. My partner, Kim Kitsuragi, was not only an invaluable partner and fantastic human-being (I knew him for two whole minutes before I swore to kill anyone who harmed him), but a natural repository for the world’s lore, thanks to you being an amnesiac.

All throughout the story, ZA/UM ensured I’d want to know more, always showing and never telling. Who do I work for? Why is the Union boss considered a problem? Who put down the Communist uprising fifty years ago? What is the Pale? Why is this reality having a physical existential breakdown? It’s all so god damn captivating, and I spent a large portion of the game trying to learn more. Would a character tell me more about the Pale if I ran an errand for her? You bet your ass I ran that errand.

Disco Elysium is the rare instance of world-building and narrative not only peacefully coexisting, but complimenting each other. With every story beat I’d want to learn about Elysium, and with every new lore tidbit I’d want to push the story. Backed by the solid writing I already mentioned I’d argue Disco Elysium has not only one of the best stories this year, but in the genre as a whole (right up there with Planescape: Torment, even).

The gameplay side of it all flows together smoothly. You walk or run with the mouse, highlight objects in the environment with tab, and have a minor character sheet you can manage with clothing found throughout the game that provide minor statistical buffs and debuffs. The numbers side of the experience, the video-gamey aspects of Disco Elysium, never undermine the role-playing; all of it works in concert. Your skills may talk you constantly, but you still need to level them to pass skill-checks. Figuring out which you want to focus on is wholly on you, but you can’t master everything, nor pass every check. ZA/UM begs you to find your character and to stick to that role. Even combat is handled via a dialogue window and dice roll: this is as pure a role-playing experience as one can have.

To make it all work you essentially walk around and interact with people, observe the world around you, and ultimately try and piece together the reason behind the murder you were called in to investigate. The game embraces its core detective concept by having you talk to everyone. I mean that almost literally (because, as I’ve noted, you can approach this game damn near any way you want). Following up a clue with one character may cause them to clam up under the pressure, making a skill check difficult. Go talk to a friend of theirs, though, and you may find out why they are nervous and receive a bonus to that skill-check that makes it easy.

You are encouraged to poke around and learn as much as you can in Disco Elysium, because all those choices you make can affect and modify skill-checks. Changing clothing can give you the edge you need as well. This is a game that wants players to poke around, explore, and learn as much as they can; just be ready to deal with whatever repercussions come your way. ZA/UM wants you to step to their groove, get into character, and let loose in Martinaise. The fact that every element of the experience clicks together isn’t merely commendable, it’s amazing.

The Verdict

It’s here I feel I need to bring this all to a conclusion, otherwise I’ll keep rambling and gushing about it. Disco Elysium is perhaps one of the best role-playing games of all time, and I don’t say that lightly. I haven’t played a game that has been able to so masterfully flex to my actions as well as ZA/UM’s freshman outing. The writing is sharp, the characters genuine, and the choices possess true stakes. I never once felt like I was walking down a single path towards the conclusion, one where my decisions were simply different colored cobblestones on the left leading to the same destination as the other colored cobblestones on the right.

Disco Elysium made me feel joy, regret, and hope. At every turn I felt like it was my story I was telling, and the game guided me along, accepting my failures and success in turn. I was never pigeon-holed, and I was never forced to do anything. I could always walk away, or do something different based on my particular choice of character. I may not have liked every option, but it always felt earned. Every element of Disco Elysium coalesces into a suburb whole, and I desperately wish, like the protagonist, that I could purge my memory of it and re-experience it once more with virgin eyes and clear mind.

Published: Dec 12, 2019 06:01 pm